Introduction

Pain, swelling, stiffness, or a buckling sensation in the knee can signal the presence of a wide variety of conditions or injuries that may affect the general population. But patients who injure or aggravate their patellofemoral joint, where the end of the femur (the long bone in the thigh) meets the patella (the kneecap), or those who develop arthritis in this portion of the knee only, often have specific complaints such as pain with stairs especially descending, pain with prolonged sitting, and pain going from a sitting to a standing position. They may also have anatomical features that put them at risk for their condition.

Seeking prompt medical attention for injuries or diseases that affect the patellofemoral joint can help assess the degree of risk present and minimize or prevent further injury.

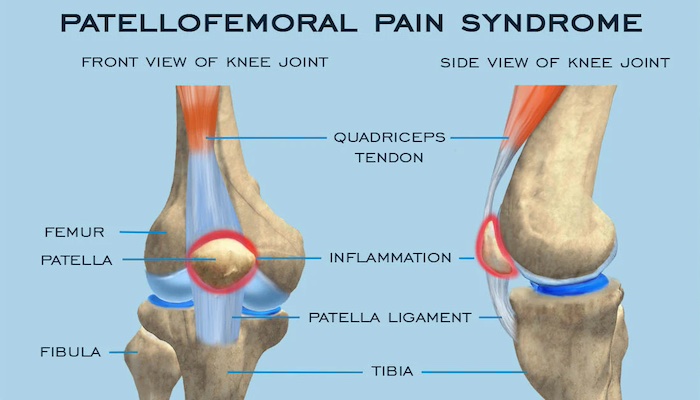

In the healthy knee, the bones that make up the patellofemoral joint move smoothly against one another as the joint is bent or extended, with the patella gliding in a groove or trochlea of the femur (the groove may also be referred to as the sulcus). One of three compartments in the knee, together with the lateral compartment on the outside of the knee and the medial compartment on the inside, the patellofemoral joint is supported and stabilized by a complex network of ligaments, tendons, and other soft tissues.

Problems affecting the patellofemoral joint most frequently include pain, instability (subluxations or dislocations of the patella - when the kneecap moves partially or fully out of the groove in the femur), and arthritis.

Patellofemoral pain syndrome describes pain in the patellofemoral joint (kneecap and front part of femur) that is due to overuse rather than a traumatic injury. Although this pain may first become apparent during athletic activities such as running, it is also evident with everyday activities. Patients often notice it when going up - and especially downstairs, after sitting for a long time, with the transition from sitting to standing, and when squatting, kneeling, and lunging. Wearing high heels can also exacerbate symptoms. The pain is usually less pronounced when walking on level ground.

Other names for patellofemoral pain syndrome include chondromalacia patella (a reference to the degeneration of cartilage in the kneecap) and runner’s knee or moviegoer’s knee.

The pain is often found at the lower and outer margins of the kneecap - underneath the patella and outside of the knee. However, patients may also experience pain more diffusely over the whole joint when there is more severe inflammation.

Patients with this syndrome have an uneven distribution of stress or load underneath the kneecap that is causing pain. Sometimes, this is due to an abnormal tilt of the patella which can be seen on X-rays but it can also be seen in the setting of normal X-rays secondary to weakness in the large muscle groups of the leg. “It’s as if the joint is like a seesaw that has too many children on one side. That extra stress on that side of the seesaw is similar to what one area of the knee is subject to every time you bend and straighten the joint.”

Because patellofemoral pain inhibits the quadriceps muscle (the major muscle in front of the thigh) from doing its “job” of unloading stress on the kneecap, once pain occurs, it often progresses.

Patellofemoral pain syndrome - as well as other problems with the patella - are seen far more frequently in women than in men. Women naturally stand and squat in a more valgus or knock-kneed position, a posture that automatically pulls the patella toward the outside of the leg and places the knee at risk for this uneven stress distribution.

Overly tight muscles and soft tissues that support the knee, including the hamstring muscles and the iliotibial (IT) band (the connective tissue that runs down the outer side of the thigh to the patella), can also lead to the condition. Conversely, women with hypermobile, loose soft tissues can also develop the syndrome owing to weakness and the failure of supporting muscles to balance or unload the patella, thereby allowing it to be pulled laterally away from the trochlea.

Orthopedic surgeons and sports medicine specialists evaluate patellofemoral pain with a thorough physical exam which includes the assessment of any imbalances that may be present from the feet to the hips. In addition to a tilted patella, pain can be exacerbated by other factors that place extra stress on the bone including flat feet, abnormal rotation of the hips, tightness of the IT band, and hip flexors. MRI and X-ray images are often obtained to assess the bones, alignment, and cartilage surfaces of the kneecap and trochlea.

Treatment

The majority of people with patellofemoral pain syndrome can be treated non-operatively. The first goal of treatment is to “quiet the knee” with anti-inflammatory medications, application of ice, and relative rest. Patients must also alter any activities that are exacerbating the condition, avoiding participation in impact sports, high-intensity workouts, squats, or lunges, and minimizing stair climbing, at least temporarily. In cases where an anatomical issue such as flat feet plays a role, orthotics may be prescribed. In patients who run, if irregularities in landing - such as pronation or supination - are contributing to the pain, a different shoe may be required. In some cases, a cortisone injection may be helpful to decrease inflammation in the knee so that the patient can tolerate a stretching and strengthening program.

A physical therapy regime is initiated to loosen tight tissues if present, and to improve structural strength throughout the leg and hip. In some cases, when physical therapy doesn’t yield the expected improvement, further imaging is obtained such as MRI with specialized sequences to detect early cartilage changes. Occasionally a running analysis is performed, as it may reveal an underlying gait abnormality that needs to be addressed.

Some patients seeking care for patellofemoral pain syndrome do so owing to persistent pain after undergoing a surgery called a lateral release. This is a fairly simple procedure in which the surgeon uses a small camera and instruments to release the retinaculum, the tissue that acts as an envelope around the knee and runs along the outside of the joint. Continuing pain indicates that other factors contributing to the syndrome have not been addressed.

The lateral release can be helpful in conjunction with a larger surgery such as a tibial tubercle osteotomy or a medial patellofemoral ligament (MPLF) reconstruction as part of the overall soft tissue balancing, but as an isolated procedure, it is appropriate for only a very small subset of patients. These include individuals who have a tilted patella and intact cartilage, and who have not responded to extensive physical therapy. This is the overwhelming minority of patients with the syndrome, more than 95% of these patients do not require surgery.

Patellofemoral Subluxation and Dislocation (Kneecap Instability)

Patients who have a tracking problem in the patellofemoral joint - the patella does not stay in the groove on the femur - are vulnerable to a spectrum of conditions. These include subluxations, in which the patella slips partially but not completely out of the trochlea, as well as dislocations, a traumatic injury in which soft tissues are damaged as the patella completely “jumps” the track and then comes forcibly back into place. Because the bone always dislocates outward, the ligament on the inside - the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) tears or stretches.

People who experience a first-time patella dislocation frequently do so while participating in sports, causing the knee to suddenly buckle and fall. Because ACL tears often happen in the same way, and because they are much more common than patella dislocations, it is important to rule out an ACL tear. In rare cases, a patient comes in with an ACL tear and is found to have had a patella dislocation as well.

Physical signs of dislocation include significant swelling of the knee and an “apprehension sign”, an anxious response to the orthopedists translating the patella outward and attempting to mimic the dislocation. An MRI after kneecap dislocation reveals damage to the ligament, and bruises on the bone inside of the patella and on the outside of the femur that occur when the kneecap “re-locates” back in place. The MRI is also helpful in evaluating the knee for evidence of cartilage injury which is very common after dislocations.

Risk Factors for Dislocation

People at risk for subluxation and dislocation include both young women who are loose-jointed, as well as athletes who may experience a more traumatic dislocation while playing their sport. (Subluxation and dislocations do occur in men and boys but much less frequently.) Individuals in these groups share in common specific anatomic variations that are now widely recognized as risk factors. These include;

- a shallow (or even absent) groove on the trochlea or femur

- an abnormal insertion of the patellar tendon on the tibia (shin)

- knock knees

- high riding kneecap

In the case of a shallow groove (track), the patella is not as well-controlled as it is by the deep groove that is present in a normal patellofemoral joint. As a result, less energy is required to force the patella from its track.

Patients with malalignment that results from a knock-kneed posture are subject to a greater than normal force on the patella, which pulls the bone outward, out of the trochlear groove, and toward the outside of the knee. In a normal knee, the tendon that connects the patella to the tibia maintains a force that is in line with the patella, (tracking in alignment with the trochlear groove). Orthopedists use the TT-TG (tibial tuberosity trochlear groove) index to measure the degree of malalignment present and guide treatment recommendations.

Individuals with patella alta, a patella or kneecap that is located higher up on the femur than normal are also at increased risk of dislocation, as the patella must travel a greater distance during flexion of the knee before engaging fully in the groove or track of the femur. The joint is particularly vulnerable to instability during this period.

Although dislocation is very painful, after the knee quiets down and returns to baseline, there may be little to no pain in between the instability episodes. Pain and instability don’t always go hand-in-hand. This can be problematic since pain-free patients may delay seeking treatment despite recurrent episodes of instability while cartilage damage continues to progress with each dislocation or subluxation.

Treatment

The standard of care for first-time dislocations is non-operative treatment, where we allow the torn ligaments to heal on their own. However, an MRI is important to evaluate the degree of damage that has occurred even after one dislocation. Surgery is necessary if a piece of bone or a piece of cartilage has been dislodged, resulting in a loose body - as these can cause locking, buckling, or additional pain in the knee if left untreated. This type of injury may also be referred to as an osteochondral fracture. In these patients, surgery is performed to both remove the loose body or repair it and stabilize the patella at the same time.

In patients who do not require surgery, the knee is commonly immobilized in a splint or brace for a few days or weeks to allow the knee to calm down and for swelling and pain to subside. The orthopedist may also drain fluid from the knee to reduce discomfort at the first office visit if there is considerable swelling. Physical therapy is the primary course of treatment after a first-time dislocation and is started within the first 1-2 weeks after the dislocation, to achieve normal range of motion and strength. Physical therapy after a dislocation usually continues for between 2-3 months and it can take as long as 4 -5 months for some athletes to return to their pre-injury level of play.

Once a patient has dislocated his or her patella or knee cap, he or she is at an increased risk of it happening again whether it is in the form of subluxation or a full dislocation. Although injured ligaments do “fill in” and heal during recovery, these structures are generally stretched from the injury and are less able to control the patella - further contributing to the risk of another instability episode.

Statistics show that this risk of having another dislocation or subluxation after a first-time dislocation is somewhere between 20-40%; and that after the second dislocation, the risk of recurrence goes up to greater than 50%. Younger patients (under the age of 25) are at even greater risk, especially those in whom the growth plates (a site at the ends of the bone where new tissue is produced and bone growth continues until skeletal maturity) are still open with radiolocation rates reaching 70%.

Surgery to stabilize the knee cap is recommended for individuals who have experienced more than one dislocation. Not only do we want to stabilize the knee so that the patient can get back to sports or daily activities, but even more importantly, we want to protect the cartilage underneath the kneecap to prevent arthritis from developing in these generally young patients. Cartilage damage can occur with every instability event and statistics show that some damage is apparent on MRI in more than 70% of cases.

Depending on the underlying risk factors for instability, the orthopedic surgeon may perform either a soft tissue or a bony procedure. Soft tissue procedures involve either repair - or more frequently reconstruction - of the torn medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL).

Repair of the ligament may be possible if the patient seeks treatment promptly and has not experienced any previous dislocations. But in most cases, the orthopedic surgeon takes tissue from elsewhere (usually a hamstring tendon) either from a donor or the patient’s body, and constructs a new ligament.

Bony procedures or realignment surgery is advised when the patient has an anatomical abnormality in which the patella tendon attaches to the tibia in such a way that there is a severe pull on the patella sideways or laterally. To correct the alignment, the orthopedic surgeon moves a small portion of bone where the tendon attaches and repositions it to a location on the tibia that eliminates the lateral stress and allows the tendon to guide the patella effectively into the groove. This surgery is called an osteotomy or a tibial tubercle transfer.

Osteotomy also helps to compensate for the risk associated with a high patella (patella alta). By repositioning the tendon to a more optimal placement, the surgeon can “lower” the patella to the proper level, thus bringing the patella closer to the upper trochlear groove, and reducing the distance it has to travel to enter the groove. This minimizes the risk of patellofemoral subluxation or dislocation at the early stages of flexion.

This type of surgery produces good results but is not a procedure that can be performed in young people with open growth plates. For these patients, the surgeon may choose to brace the patient until the growth plates close or if they feel the patient to be at significant risk for repeated dislocations then they may choose to do the soft tissue operation to reduce the risk and then wait until the growth plates close to do the tibial tubercle transfer (bony surgery). In some patients, both a soft tissue and a bony procedure may be appropriate. Both surgeries yield very reliable results in stabilizing the knee with an 85-90% success rate.

Patients with patellar instability due to mal-alignment usually have problems in both knees, whether they have dislocated both joints or not. If the patient has experienced a dislocation in both knees, the orthopedist will address the knee that is more severely affected first, and then stabilize the other one later to prevent cartilage damage.

Recovery from knee stabilization surgery takes from 6 to 9 months and involves both extensive physical therapy and activity modification.

In patients who have damaged or lost some cartilage as a result of one or more instability events, the orthopedic surgeon may recommend a procedure to repair or regenerate the damaged cartilage that lines the joint. While no method works perfectly, patients with cartilage defects resulting from instability are more likely to benefit from current cartilage repair techniques than patients with generalized osteoarthritis of the knee.

“In a traumatic event like a dislocation, if cartilage damage occurs, it usually means that an isolated chunk or piece of cartilage has come off and that the rest has remained pristine. Filling in this defect with either cartilage from another part of the patient’s knee or donor tissue can be an effective treatment option.”

The comparatively predictable good results of knee stabilization procedures are just one reason orthopedic surgeons emphasize the importance of stabilizing the knee before cartilage damage occurs or progresses. However, research in cartilage regeneration continues to be active and is showing promising results.

Patellofemoral Arthritis (Kneecap Arthritis)

Like patellofemoral pain syndrome, patellofemoral knee arthritis is characterized by pain and stiffness and often swelling in the front part of the knee that typically worsens on walking on inclined terrain, going up and down stairs, squatting, or rising from a seated position.

Patellofemoral arthritis is diagnosed when there is a significant loss of cartilage from the joint surface of the patella and the trochlea (groove). The diagnosis is restricted to arthritis seen only in this compartment of the knee; if the medial and lateral compartments are affected, generalized osteoarthritis of the knee is the likely diagnosis. (As with other disorders of the patellofemoral joint, it is more frequently seen in women.

People who develop patellofemoral arthritis generally receive one of three diagnoses:

- post-instability arthritis is the result of cartilage damage that occurs with multiple dislocations or subluxations in the joint

- post-traumatic arthritis, cartilage damage that results from a fall or other traumatic injury to the knee that then progresses over time to arthritis, or

- overload osteoarthritis, a condition that resembles osteoarthritis in any other joint, i.e., a gradually progressive thinning of the cartilage related to “normal wear and tear” that in this case is restricted to, or starts in, the patellofemoral compartment of the knee.

Treatment

Treatment for patellofemoral arthritis always begins with non-operative measures. These include adaptations in activity, such as avoiding stairs, limiting squats and lunges, and decreasing impact sports; physical therapy to stretch and strengthen surrounding muscles; and use of medication such as acetaminophen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to relieve pain.

For patients with mild to moderate arthritis who are experiencing an acute flare of their condition with swelling, steroid injections, which reduce inflammation, can be effective. Good results are also being seen with viscosupplementation, in which a substance that mimics naturally occurring synovial fluid is injected into the joint to help lubricate it and minimize friction. In patients who are overweight, weight loss can help reduce the amount of stress applied to the knee. Bracing the knee is generally not helpful in people with patellofemoral arthritis.

People with patellofemoral arthritis who do not respond to nonsurgical treatment may be candidates for a partial knee replacement, also called a patellofemoral joint replacement or noncompartmental knee replacement. This procedure, allows the orthopedic surgeon to replace only the affected area of the knee, the patellofemoral joint, and to leave the healthy medial and lateral compartments intact. (Uncompartmentalized surgeries to address arthritis in each of those compartments are also an option for patients with arthritis in those portions of the knee.)

During this procedure, the orthopedic surgeon removes the damaged cartilage and a small amount of bone from the joint surface of the patella and replaces it with a cemented high-density plastic button or patella implant. Damaged cartilage and a small amount of bone are also removed from the joint surface of the trochlear groove, which is replaced with a very thin, metal laminate that is cemented in place. The goal is to eliminate friction and restore a smooth gliding motion in the joint.

Orthopedic surgeons are now achieving excellent results with patellofemoral joint replacement, results that are comparable to those achieved with a total knee replacement.

In addition to partial knee replacement, patients with post-instability arthritis due to mal-alignment may also require soft–tissue procedures and/or osteotomy or tibial tubercle transfer surgery (described in the section on patellar instability) to realign the knee. This mitigates the possibility of subsequent dislocations. Patients who require more than one procedure may have them done either in stages or during a single operation.

Determining whether the arthritis is the result of an alignment issue, or whether it is the beginning of an ongoing process that will eventually affect the entire knee is extremely important. Patients who do best with patellofemoral joint replacement are those in whom the arthritis is not expected to progress: those with post-instability arthritis and those with post-traumatic arthritis, “These are patients who are unlikely to ever need a total knee replacement."

Many of the patients are patients without a history of instability or trauma. They have isolated patellofemoral arthritis where it is likely the first or early presentation of osteoarthritis which may progress at some point to involve the rest of the knee. These are typically women in their 50s or 60s who experience pain and stiffness during certain activities and transition from sitting to standing. The knee is not painful with all activities and they can walk on level surfaces without discomfort. While the symptoms are restricted to the patellofemoral compartment at the time of diagnosis, some arthritic changes may be observable in images of the rest of the knee.

When I discuss surgical options with these patients, I let them know that although a patellofemoral knee replacement will address their symptoms, we can’t know with absolute certainty whether they will eventually require a total knee replacement. However, there are numerous advantages to partial knee replacement, including a much faster recovery, and the sensation that the knee still feels ‘normal.

For many of these patients, the promise of a decrease in pain and an improvement in function for years to come is acceptable. If a total knee replacement becomes necessary, their partial knee replacement will not compromise the results of this subsequent surgery.

Seeking Treatment for Patellofemoral Disorders

With a range of effective non-operative and surgical procedures available, people with patellofemoral disorders now have a better chance of returning to pain-free function than ever before. However, because patellofemoral pain and instability can easily progress to patellofemoral arthritis if left untreated, individuals with these symptoms are advised to seek early evaluation.

To help ensure a good treatment outcome, look for an orthopedist who specializes in patellofemoral disorders. Finding an orthopedic surgeon trained in sports medicine is a good place to start.

Precision Pain Care and Rehabilitation has two convenient locations in Richmond Hill – Queens, and New Hyde Park – Long Island. Call the Queens office at (718) 215-1888 or (516) 419-4480 for the Long Island office to arrange an appointment with our Interventional Pain Management Specialist, Dr. Jeffrey Chacko.