While no single test can definitively diagnose osteoarthritis of the knee, physicians use a comprehensive approach that is verified by diagnostic imaging to arrive at a clinical diagnosis.

It is important to clarify that most individuals over age 50 will have signs of osteoarthritis in their major joints that can be seen on an x-ray, but most will have no symptoms, so the medical provider will not rely on diagnostic studies (such as an x-ray or MRI) alone. An accurate diagnosis will come following a comprehensive medical history and physical examination by the healthcare provider.

Below is a description of the process physicians use to determine if a patient’s symptoms are caused by osteoarthritis.

Patient interview: A doctor will ask a patient about family history and to describe the onset of his or her knee symptoms, the pattern of pain and knee swelling and how symptoms affect lifestyle, as well as what makes the pain better or worse. A patient’s reported symptoms are important for diagnosis and treatment.

Physical exam: A doctor will physically examine the patient’s knee, noting any signs of swelling, pain points, stiffness and range of motion. The examination should extend above and below the knee since knee pain may be referred from a remote source (i.e. referred down from the lower back).

Testing: After the patient consultation and physical exam, the doctor will usually have a pretty solid determination if the patient’s symptoms are caused by arthritis or not. Follow up tests may be included as part of the diagnostic process both to gain further information about the extent of the knee arthritis and/or to rule out other possible causes of the patient’s pain.

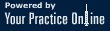

X-rays: X-rays can show if there is a loss of joint space between the femur and tibia, indicating a loss of cartilage in the knee. An x-ray can also show bone spurs, a sign that the bones have tried to compensate for cartilage loss with extra bone growth. However, some people may have x-rays that show significant signs of knee osteoarthritis and experience no pain, while others may have x-rays that show few signs of knee osteoarthritis and have significant pain. Minor cartilage damage or bone spurs can translate into a lot of pain if either is in a sensitive spot. Therefore, the x-ray is just one tool to be used in conjunction with the patient interview and physical exam.

MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) may be ordered to provide additional detail, as this test provides images of the soft tissue (ligaments, tendons, and muscle) as well as bone. This more detailed image of the knee joint can be helpful if x-rays of the knee are inconclusive or if the doctor suspects symptoms are due to something other than the osteoarthritis, such as damage to the knee’s meniscus, tendons or ligaments. However, an MRI is more time consuming - requiring the patient to remain perfectly still for about 30 minutes - and is much more expensive than an x-ray. An MRI is not necessary in most cases.

Lab tests: Lab tests cannot identify the presence of knee osteoarthritis, but they can be used to rule out other problems, such as infection or gout that can also cause knee pain. Lab tests may require a blood draw or an aspiration of the knee joint (taking fluid from the joint).